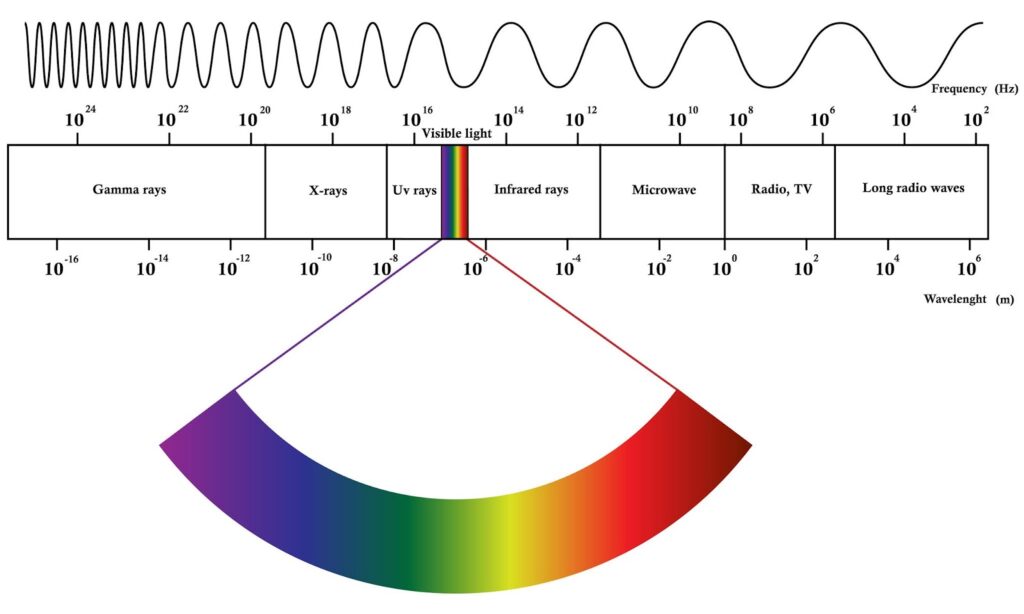

Radio waves are on the same frequency as microwaves, infrared, visible light, UV light, X-rays, and gamma rays, in that order:

As a wave, light moves back-and-forth. If it only moved 1 time back-and-forth in a second, it’d be 1 hertz (Hz), named after the second scientist to discover electromagnetic waves, Heinrich Hertz. 1,000 times a second is 1 kilohertz (kHz), 1,000,000 times a second is 1 megahertz (MHz), and 1,000,000,000 times a second is 1 gigahertz (GHz).

As the frequency increases, the wavelength decreases. The relationship between them is directly correlated, demonstrated by the physics calculation of (wavelength x frequency = speed of light). For the sake of engineering, frequency is used the most.

The Doppler effect is the relative shift in frequencies due to speed differences. It also applies to other waves (e.g., sound), and shows when sending and receiving radio signals operate at different speeds. This is essentially how radar speed guns work, where it reads the relative variance between its transmitted and received frequencies.

One of the most frequently used implementations of radio is for detecting and determining distance from somewhere else, also known as “radar”. Most geolocation uses multiple radio towers with variations of radar protocols to more precisely determine a device’s location than simple satellite coordination.

There are many, many frequency allocations in the United States. The US’ FCC guidelines separate the signals and make specific signal strength limits, which permits signals to not disrupt each other across different uses:

- 9-535 kHz: exclusively mobile communications, radiolocation, and radionavigation for aircraft/ships

- 535-1705 kHz: AM radio (if those numbers didn’t seem familiar)

- 1705-5005 kHz: general radiolocation, aircraft/ship mobile, and amateur radio

- Standard frequency/time signal at 5 MHz (4.995-5.005)

- 4.995-9.95 MHz: mix of TV broadcasting channels 5/7/9, aircraft/ship mobile, and amateur radio/satellite

- Standard frequency/time signal at 10 MHz (9.995-10.005)

- 10.005-14.99 MHz: mix of TV broadcasting channels 11 and 13, aircraft/ship mobile, amateur radio, radio astronomy

- Standard frequency/time signal at 15 MHz (14.99-15.01)

- 15.01-19.99 MHz: mix of TV broadcasting channels 15/17/18, aircraft/ship mobile, and amateur radio/satellite

- Standard frequency/time signal at 20 MHz (19.99-20.01)

- 19.99-24.99 MHz: TV channel 21, aircraft mobile, amateur radio/satellite

- Standard frequency/time signal at 25 MHz (24.99-25.01)

- 25.01-50 MHz: mostly mobile and land mobile allocations interspersed with ship mobile, TV channel 26, and radio astronomy

- 50-54 MHz: amateur radio

- 54-88 MHz: TV broadcasting, with a small aircraft navigation and radio astronomy band in between

- 88.0-108.0 MHz: FM radio (if those numbers didn’t seem familiar)

- 108-137 MHz: aircraft radionavigation/mobile

- 137-138 MHz: space-to-earth satellite communication

- 138-174 MHz: mix of satellite radionavigation/mobile, amateur radio/satellite, and ship/land mobile

- 174-216 MHz: TV broadcasting

- 216-400.05 MHz: mix of land/satellite mobile and aircraft/satellite radionavigation

- Standard frequency/time signal at 400.1 MHz (400.05-400.15)

- 400.15-420 MHz: space-to-earth and earth-to-space satellite communications, radio astronomy, and radiosondes (radio communications from weather balloons)

- 420-450 MHz: amateur radio and radiolocation

- 450-960 MHz: land mobile and TV broadcasting with a few bands for radio astronomy, aircraft mobile, and radiolocation

- 960MHz – 300 GHz: a vast range of radionavigation, various satellite bands, wireless networks, radio astronomy, space research/operations, amateur radio, and radiolocation

- Up near the top end of the spectrum, more frequencies are allocated to radio astronomy.

- And, sandwiched throughout everything are many, many mobile cell phone allocations, with a few reservations for government-only communication.

On this spectrum, Bluetooth signals sit at 2.4 GHz and Wi-Fi at 2.4 and 5 GHz, but they don’t show up on the chart because they don’t broadcast very far. 2.4 travels through materials better than 5, so it’ll never be a completely obsolete standard for wireless internet.

Ham radio operators are the only people allowed to use devices that go across multiple radio frequency spectra, but they need a few tiers of certification before they can operate them.

Shortwave broadcasts will always be useful because they’re often the only way to communicate in an emergency.

Wireless Information

One of the newest forms of wireless transmission is through the IEEE’s 802.11 standard.

At first, the transmitter/receiver configuration (“transceiver”) were “single-input single-output” (SISO) with a one-at-a-time approach, but slowly became “single-user multiple-input multiple-output” (SU-MIMO) and finally became “multiple-user multiple-input multiple-output” (MU-MIMO).

It’s worth noting that wireless networks are always operating as “hubs”, so “carrier-sense multiple access” (CSMA) is a constant need to keep the signals organized. The extra complexity and conflicts with managing multiple streams of network traffic is a considerable reason why wireless can never quite get wired signal speeds.

There is a lot of error-correcting code to compensate for radio signals, for several reasons:

- Signals can easily get mixed with other signals, so the code is sent many times, and often repeatedly until it receives a signal back.

- The order of the signals won’t reach the target at the same time, since some signals bounce off surfaces or travel through different media (e.g., a wall, water).

While it’s not always possible, the best travel on signals comes through a direct line of sight combined with sufficient “gain”. There are several ways to amplify gain:

- Use a bigger antenna to increase the broadcast range.

- Use a directional antenna. You can create a dish out of aluminum foil to improvise.

- Send a stronger signal, which may involve boosting the computer itself or using an array or repeater.

Wireless standards have evolved as the technology has gotten better:

- 802.11b was the first 2.4 GHz standard.

- 1×1 (1-to-1) SISO, 22 MHz channel bandwidth, 2.4 GHz band

- 802.11a was the first 5 GHz standard.

- 1×1 SISO, 20 MHz channel bandwidth, 5 GHz band

- 802.11g was made to be faster and go a longer distance than 802.11a

- 1×1 SISO, 20 MHz channel bandwidth, 2.4 GHz band

- 802.11n was necessary to connect more devices to the internet, including smartphones, with High Throughput (HT).

- 4×4 SU-MIMO, 40 MHz channel bandwidth, 2.4/5 GHz bands

- 802.11ac created enhancements for Very High Throughput (VHT) to accommodate everyone’s demand for home Wi-Fi.

- 8×8 DL-MU-MIMO (Downlink MU-MIMO, which allows the transmission to happen at the same time), 160 MHz channel bandwidth, 5 GHz band

- 802.11ax created High Efficiency (HE) Wi-Fi.

- 8×8 MU-MIMO, 160 MHz channel bandwidth, 2.4/5/6 GHz bands

- 802.11be enhanced throughput even more to Extreme High Throughput (EHT)

- 16×16 MU-MIMO, 320 MHz channel bandwidth, 2.4/5/6 GHz bands

At the same time, streaming devices needed separate standards:

- 802.11ad was needed for in-room and desk network applications that needed a lot of data transfer (e.g., video streaming).

- Directional multi-gigabit (DMG) 1×1 SISO, 2.16 MHz channel bandwidth, 60 GHz band

- 802.11ay is a high-data, long-distance standard for a wide variety of uses.

- 8×8 MU-MIMO, 8.64 MHz channel bandwidth, >45 GHz bands

IoT had to have a separate sub-GHz spectrum for their low-data long-range needs:

- 802.11af was for Television Very High Throughput (TVHT)

- 4×4 DL-MU-MIMO, 6/7/8 MHz channel bandwidths, <1 GHz band

- 802.11ah is a licensing-exempt standard (meaning anyone can use it without notifying a governing authority).

- 4×4 DL-MU-MIMO, 1/2/4/8/16 MHz channel bandwidths, <1 GHz band

Furthermore, autonomous vehicles have their standards as well to accommodate continuous bandwidth:

- 802.11p was Wi-Fi-based car-to-car communication to allow intelligent traffic services.

- 1-to-1 SISO, 10 MHz channel bandwidth, 5.9 GHz band

- 802.11bd enhanced 802.11 p for next generation vehicular (NGV) devices.

- 2-to-2 SU-MIMO, 10/20 MHz channel bandwidths, 5.9/60 GHz band

Risks

Electromagnetic waves are typically only harmful when they can penetrate skin. UV rays can somewhat penetrate beyond the epidermis, and X-rays and gamma rays go right through us.

On the other end, most short-wave non-visible light can’t harm us, at least in the short term. Microwaves, in particular, are still harmful because they’re precisely the right frequency to penetrate skin, which can transfer heat energy (i.e., how microwave ovens work).

Since our bodies are bioelectrical systems, electromagnetic interference is a legitimate risk, though there hasn’t been much research into the long-term effects of being near radio. However, a 2012 report does indicate there are long-term risks to electromagnetic radiation.

Further Reading

The United States Frequency Allocation Chart